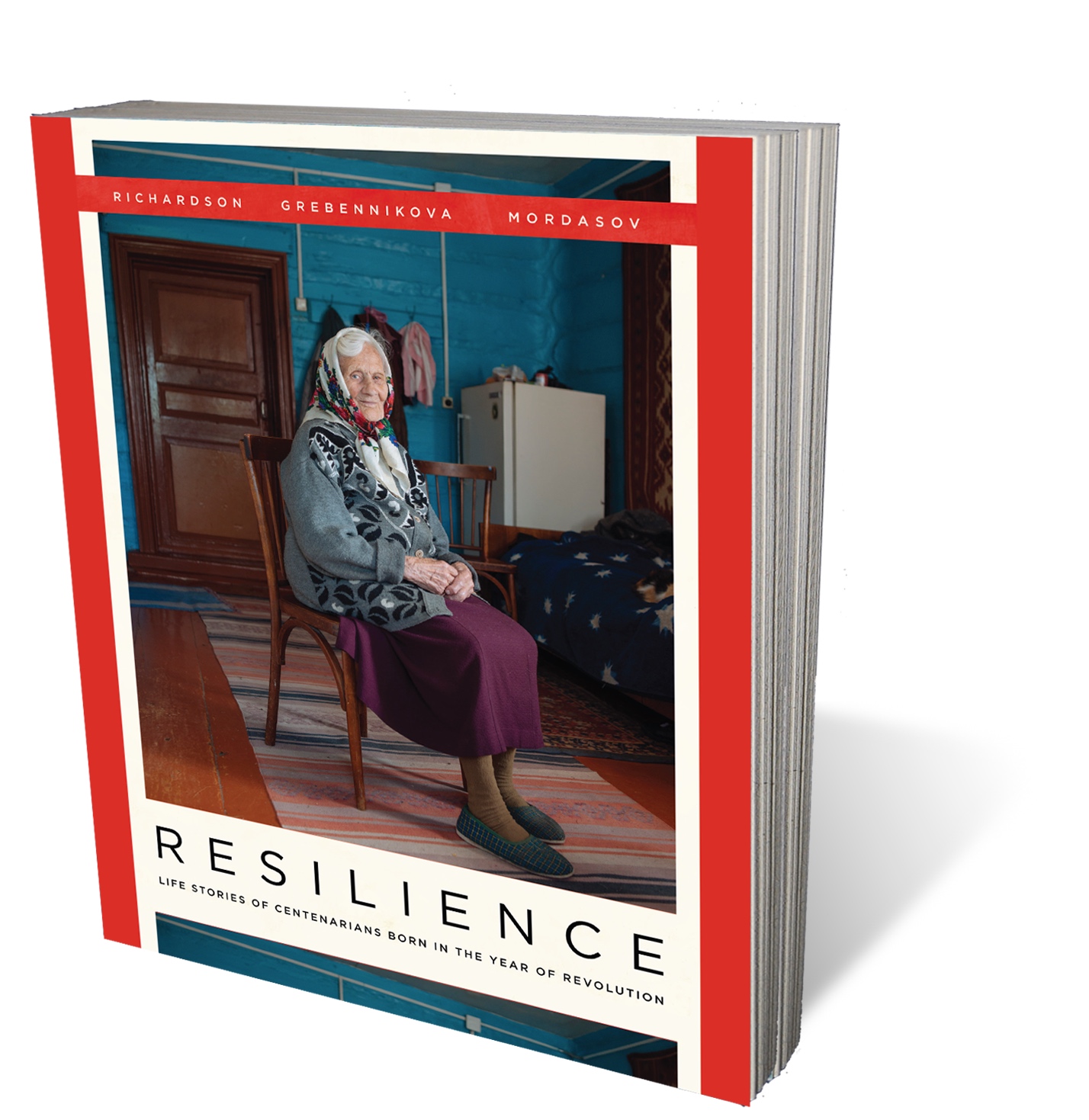

Mikhail Mordasov

Lyubov Ivanovna Pakhomova

- Jan 12, 2018

- Paul Richardson

Born 2 August 1917

Pokrovka Village, Novosibirsk Oblast

To get to the village of Pokrovka from Novosibirsk requires a 250-kilometer, four-hour drive over gut-pounding roads. The broken, humpy asphalt trails through wide, open fields of knee-high wheat (it grows shorter here) that are broken by lines and copses of birch and capped with tremendous cloud structures left behind by the previous day’s storm. Numerous raptors are sighted circling the fertile, rodent-filled fields, or perching atop telephone poles or rolls of hay.

The village – just a stone’s throw from the border with Altai Krai, was once part of a thriving kolkhoz. But now it is empty, save for three families. An abandoned village store, topped by a rusting satellite dish, sits on the edge of an overgrown field. At the other end of the field, bordering a horse paddock, is a slowly crumbling monument to those who fell in World War II.

Opposite the shuttered store is the only home in the village that shows any evidence of life. And here it is in abundance. A hand-painted sign warns of dogs behind the fence, and there are three, all of them chained up. One is a shaggy dog about half the size of the dozen broiler chickens roaming the yard; the second is a puffy, squeaking puppy full of rambunctious energy; the third is a large German Shepherd who sounds fierce but is, in fact, a marshmallow that would just love to crawl into your lap.

The log and plank outbuildings (shed, banya, outhouse) are run-down but solid. Between the garden and the home’s front door is an overstuffed chair infested with kittens.

The house itself is small but solidly built. It was erected long ago for a school director, and it has the inviting feeling of a home where every corner is put to use, combined with the awkwardness of a century-old design that is somewhat inappropriate for modern living.

Lyubov Pakhomova, fully blind and nearly deaf, sits on a couch at one end of the large family room, clearly anticipating visitors.

“Some guests are here to see you,” Lyubov’s granddaughter-in-law Irina announces.

“Have you come for me?” Lyubov replies.

Irina smiles, patient and reassuring, “No, no, babushka, No one is taking you anywhere. They are guests.”

Before Lyubov moved in with Irina and her husband Nikolai, she was living in a neighboring district with her daughter. When the daughter passed away, Lyubov said to Irina and Nikolai, “Take me to an old folks’ home, you don’t need to be worrying about me.” The couple scoffed at the idea and scolded Lyubov for even thinking such a thing. And they brought her back to Pokrovka, to live with them and their teenage daughter, Alexandra, in the village where Lyubov had lived most of her life.

Mama had many children – 12, but only six lived to grow up. I had a brother born in ’05, a sister in ’08, me in ’17, a brother after me in ’20, another in ’22, and the last brother in ’29… We lived in Kaluzhskaya, which was a gubernia then…We were poor. The land was bad, loamy, the crops were bad. So, nothing to brag about.

We moved to Siberia in the 20s… Lenin gave the land, so whoever wanted to could voluntarily resettle in wild Siberia…*

We lived in Volchno-Burla for two years. They gave us a village so a land surveyor would show up and measure out plots for everyone. And then we moved to Pokrovka…

Our parents built a hut, and our family lived there. It was just a log hut with a grass roof that first summer. We worked like peasants, sowing, plowing, harvesting. I went to school in 192–… Oh, wait, what year was that? I was 10 or 11. And I went to school. They opened a school here…

Go to school they said. But what school? It was a sort of a collective, they called it. A collective collected there. In some sort of house… It was packed, everyone had lots of kids then… But everyone was eager to go to school.

I was born in ’17, but there were kids older than me going to school… then they sent us a young teacher, and the teenagers started harrassing her. So someone came from the regional leadership and they kicked the older kids out, but they left the younger ones who were better suited for school…

We sat four to a school desk… and back then we dressed in what we could, in what we made ourselves. Some shirt or other, a blouse, a skirt. Those were our clothes. As for shoes, some had them, others wore lapti. I wore lapti.†

Times were hard, but the family was better off in Siberia than they had been in the West. Until, that is, Collectivization arrived.

When we moved here, we were sowing by ourselves, plowing and harvesting on our own. There was bread to our heart’s content. The hunger, it was gone. In Siberia we didn’t have hunger. It was only when we lived in Kaluga Gubernia that we went hungry. We never ate pure bread. We added chaff or other things to it. But in Siberia we ate white bread…

The kolkhozes came in the 30s. It arrived here in ’30. Before that, we lived on our own, kept a bit of cattle. Sheep, cows, calves, horses – ;it was all our own…

There was a general meeting, where they explained the rules of the kolkhoz. And then they signed people up. How they signed people up, I don’t know, I can’t say. Some wanted to, some didn’t. Those who didn’t, they became kulaks… Those who feared dekulakization‡ likely signed up for the kolkhoz.

Her family was divided on whether or not to join.

Father spoke with Mother. Mother didn’t want to. I know that the women got together and broke up the meeting. They didn’t want to join the kolkhoz. Ours too. The men said that it could not be avoided, that they recommended we join. Father signed up. Those who were a bit richer, or more upstanding, they were sent off somewhere. Labeled as kulaks or fools, the devil knows what…

We had to give the kolkhoz four horses – ;three were workhorses, and there were two young foals. Then we had to give a calf or a cow. They were creating a general kolkhoz herd.

By joining the kolkhoz, the family was agreeing, reluctantly, to tie its future to the future of the farm. If it did well, they would be paid in kind, if not, they would have to make do with less. It was a radical reform of agriculture that was central to Stalin’s theory of rapid industrialization for the Soviet Union. And it would prove as disastrous as it was cruel and oppressive.

People fled. How could you live?… Some fled to Leningrad, others elsewhere. Through the river ports. They ran off to cut peat, to earn a bit. And then those people, they could not get passports. And then people demanded their passports, so they all had to return. Without a passport you can’t live, can’t get set up anywhere…

In 1941, Lyubov and two friends had reached a breaking point.

There was nothing here, nothing to eat, nothing to wear, nothing to put on your feet. And our Kaluga relatives, they had children, and they worked in peat operations. So we sent them a letter. And they proposed to us: come here, join our kolkhoz…

They planned to escape at night, and it was no small undertaking.

We finished work. I worked as a milkmaid. The other person worked as a bookkeeper at the farm. And the third worked as a groom. We decided, let’s run off, maybe we can get in at the peat operations – ;there they were earning 80-90 rubles a month, that’s what they wrote us. So we finished our workday and we decided to flee at night so that no one could stop us…

And so at night we walked 20 kilometers to the village of Reshyoty… There, we found some kolkhozniks who were driving to Kargat for fuel, and we paid one of them and he took us. And in Kargat we got tickets to Belev station in Kaluga Oblast.

It took fully two weeks to travel the 3300 kilometers by train to Belev, and to this day, Lyubov readily recalls the dates of her travel.

We left March 24 and on April 7 arrived in Yaroslavl Oblast… And they didn’t catch us on the road [for traveling without a passport]. When we arrived there they gave us a six-month passport.

How did they survive the long journey? What did they bring with them?

We took some stuff with us. We took dried bread crusts – they were sour, the flour had wormwood in it… that’s how we went and what we ate. Nothing worth noting down…

We took a change of clothes, a shirt, and a skirt.

Once they had arrived, the young women were given a modest advance, boarded in a barracks and put to work.

We dried peat. We formed it, dried it, put it in stacks so that it would dry out. There was all sorts of work. Shifting it around on pallets. Hard, that work was.

And they got paid the promised 98 rubles a month, but there was nothing extra to send back to Pokrovka, to her parents, brothers, and a daughter born in 1935. Plus, the work only lasted a few months, because two months after they arrived, the Germans attacked.

This is how we found out. We got up early, at 4, in order to get to work by 8. We got up, and there was a radio apparatus hanging there. It squawked, then stopped, then squawked, then stopped again. But we gathered around, some were joking, some were putting on their shoes, others getting dressed. And suddenly they declared that it was war. That Hitler was already bombing us.

Oy, how I had forgotten that, Lord! I tell you honestly, I had forgotten that… Kiev! They had already bombed Kiev, and they declared that it had started. June 22, exactly at 4 am, they bombed Kiev, and they declared to us that war had begun. You understand?

And yet, they had to go to work that day.

How else? But what sort of work? We hardly worked all day. Just listened. Molotov spoke. He called on all workers, all peasants, that they not let us be defeated. We… well it was like that all day. We’d work a bit, then listen to the radio. And our life flowed on. Immediately there were rations… Rations for everyone…

She worked at the peat operation until September. Since it was so close to Moscow, she and her co-workers were all evacuated, and so she returned home to Siberia, not even working a full season. For three days their train stood on a siding in Moscow, and then it traveled slowly back toward Novosibirsk.

What was the country saying? Well, they were evacuating people from around Moscow. Everyone was going somewhere, to Tashkent or wherever. Where they were headed, I don’t know. Some said things. Some said that they would not take our country. Others said that there would be chaos.

What did I think? I was awfully scared. Day and night I prayed that the hated serpent would not get to Moscow.

After returning to Pokrovka and the collective farm, life was no better – worse in fact – than when she had fled a few months before.

Everything, they said, for the front. Everything for the front. And people did not resist. Everything for the front so that we can be liberated…

We knitted mittens, socks. Sewed handkerchiefs, put them in parcels. Everyone helped out…

In 1943 she met and married her husband Nikolai, who was 18 years older than her.

His wife died in ’43 and he was alone. And I didn’t have anywhere to go. In ’42. And, well, we were acquainted and got married.

Of course, there was no real wedding.

There was nothing to eat, but we did do some celebrating.

When the war was over, all of Lyubov’s brothers returned; only one had been seriously wounded – ;his arm no longer functioned.

Victory day. We were digging in the garden. There was nothing to plow with, so we did it with our hands, digging. We had eaten some lunch, and I had two girls then. One born in ’35, the other in ’43. I had to go to work and was waiting for my niece Manya, who was coming to babysit my littlest girl.

I am waiting, looking, and for a long time nothing.

“Manya, why did you take so long?”

And she says, “Auntie, the war is over.”

And I say, “Who told you that?”

“It’s over, auntie,” she smiles. “They fed us lunch, gave us each a piece of bread with soup. And they said that the war was over.”

Oh, Lord! I look and see what is going on outside: some are waving their arms about, some are crying, and so on. So many had been killed.

We ran to each other, hugged and kissed. Everyone was happy…

That night, no one slept. We ran to visit one another, shared tears.

Then later we started to find out who returned alive… in some families, two or three had been killed. We had a family, Darya Ledankova, her husband was killed… her son disappeared, and she received the death certificate for her other son. Three… Another family, the father was killed and two sons. And others lost just one. That’s how it was…

Things didn’t get better immediately after the war.

There were shortages, hunger… Everyone suffered, but no one grumbled. You had to give them eggs, give them meat…

The family had tough times. There was a brief move out to the Rostov-on Don region, ostensibly to help keep the family of one of her daughters (Nikolai’s mother) together. But it did not work, the couple divorced, and the parents and daughter, together with Lyubov’s grandchildren, returned to Pokrovka. Nikolai recalls a rather trying childhood.

He remembers his grandfather as a sharp, difficult man who often beat him. And this cruelty may have contributed to his end. Irina shares how the daughters from her grandfather’s first marriage moved him into an old folk’s home as part of a plot to manipulate his home out from under him, to get his money.

On the other hand, Nikolai remembers his grandmother Lyuba as “the mountain” to which they all felt anchored, the rock of the family. “She never swore. She was always a very calm woman,” he says.

In her youth, Irina adds, Lyubov was told by a gypsy woman that she would live a long life, but also, that there would be grief in her life.

Which makes one wonder, why does Lyubov feel she has lived to be 100?

I don’t know. I didn’t do anything special. I lived like everyone else. And even had more of the bad. And almost none of the good…

I got sick often, got diagnosed with a nervous heart. Then, I don’t know. You think that I lived easily? Oh, my dear, there was everything: both hunger and cold, a lack of both shoes and clothing. I don’t know why I lived so long. Perhaps one just has to work more and lie down less.

Is there anything else she would like out of this life?

What then? Oh, I don’t know. To die, have a funeral, and be buried.

But not to live any longer?

To live? Yes, well, everyone wants to live. I’m living. But I need to be taken care of. Ira here, she works; Kolya also is very busy with things. And then I have to be cared for. It’s time to die, to be set aside.

* In 1920, a serious drought, exacerbated by mindless, ideologically-driven government policies, led to a horrific famine across Russia’s and Ukraine’s agricultural regions. By early 1921, Soviet power, fighting the final battles of the Civil War, was faced with massive peasant uprisings, largely as a result of the state’s expropriation of all agricultural output. The introduction of NEP (the New Economic Policy) in March of 1921 reversed government policy on agriculture and trade, and gave farmers increased freedoms and incentives to produce. As a result, by the mid-1920s, Siberia had become one of the most important agricultural regions in Russia.